Science Got it Wrong: New Data on Intensity Rewrites Longevity Guidelines

For decades, public health guidelines have operated under a metabolic assumption: 1 minute of vigorous-intensity activity (VIA) is equivalent to 2 minutes of moderate-intensity activity (MIA). This 1:2 ratio, based on estimated energy expenditure or METs (Metabolic Equivalents), focused on calorie burn rather than actual health outcomes like reduced risk of mortality and chronic disease.

New, robust research utilizing wrist-worn accelerometers from the UK Biobank is now forcing a fundamental re-evaluation, demonstrating that the true health equivalence of VIA is dramatically higher—often 4 to 10 times that of MIA. This finding validates the efficacy of short, high-intensity functional training protocols, such as those used at the X Gym, for maximizing biological age reduction.

I have known this for decades through my own observations of X Gym members, but now science finally validates it all!

The Health Equivalence Paradox

A major study published in Nature Communications tracked the physical activity profiles of approximately 73,000 adults over nearly a decade, linking objectively measured activity to major health outcomes, including all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and Type 2 diabetes [1].

The results show that the old 1:2 rule is functionally obsolete for clinical and longevity goals. When measuring actual risk reduction, the new ratios are staggering:

-

For Type 2 diabetes risk reduction, 1 minute of VIA was nearly equivalent to 9.4 minutes of MIA.

-

For CVD mortality, 1 minute of VIA was equivalent to 7.8 minutes of MIA.

-

Even for all-cause mortality, the ratio was 1 minute of VIA for 4.1 minutes of MIA [1].

This means the current gold standard of 150 minutes of MIA per week can be achieved by as little as 15-20 minutes of true VIA. At X Gym, we have known since 2001 that one of our 21-minute workouts is equivalent to about 3.5 hours of traditional training, and this study (24 years later) has validated that claim!

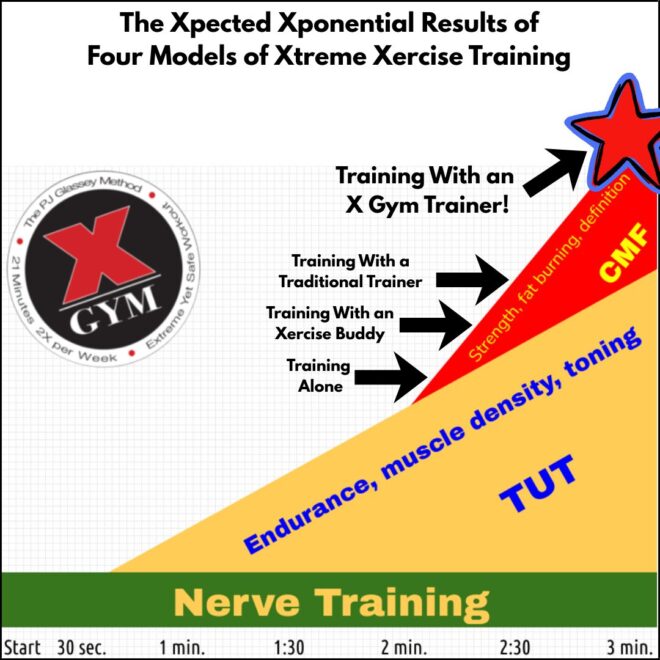

TUT, CMF and MHR spikes

The reason X Gym methodology produces better results in about 8x less time is that we are doing sets, reps, and intervals very differently from traditional training. I developed our methods: the Time Under Tension (TUT) principle, the Complete Muscle Fatigue (CMF) principle, and splinter techniques through experimentation with my own clients over a period of 11 years.

They all evolved and improved over that period of time, leading up to the X gym opening in 1998, and have evolved even further since then because we are constantly doing new experiments and discovering new studies to design these experiments.

The result is a workout that builds in intensity, thanks to TUT, and culminates in CMF at the end, two or so minutes later, resulting in a heart rate spike at the end, which turns on all the systems in the body for improvements in strength, endurance, and cardio.

Traditional sets and reps and traditional steady state cardio don’t have even close to the same effects. Because each rep has a micro rest in between, longer rests in between each set, and lower intensity, without the heart rate spike, so the heart rate doesn’t build to a max gradually and consistently. It does it with spikes and valleys along the way, which isn’t nearly as effective for results and metabolic increase.

The benefits of high-intensity training start at 1 min. That’s the minimum. Then those benefits keep increasing up to 3 minutes of TUT, and then start to level off. This is the reason for our 1-3 minute exercises, with most of them being 2 1/2 minutes to 3 1/2 minutes. Traditional sets are usually 15 seconds or less, which is great for strength results, but lousy for endurance, cardio, heart, lungs, and anti-aging benefits.

Below is a shot of my Apple Watch screen after an X Gym style strength workout. I had to use their “Traditional Strength Training” mode because there is no “X Gym” mode – yet 😉 You can see the intensity spikes and how fast I can get to 90% of my heart rate max, thanks to our unique strength training methodology.

This effect and design also occurs with our Xardio classes. Below is an example of my heart rate in one of these classes. You can see the intensity level going beyond my heart rate max, but with a different build-up than the strength training, which can only be done with our unique Xardio style.

VILPA: The Value of Micro-Bouts

The data also underscore the importance of Vigorous Intermittent Lifestyle Physical Activity (VILPA)—those short, intense bursts like sprinting up stairs or pushing hard for a minute during a quick functional training session. These “exercise snacks” are often invisible in self-reported questionnaires, yet the dose-response curve for VIA shows an almost linear, powerful benefit [1].

Even 1-3 minute bouts can substantially slash the risk of cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes, and cancer. This is another thing I have observed for years, and the reason for many X Gym APP memberships: they can select just one exercise and perform vigorous activity for 1 to 3 minutes, with all the benefits, but without the sweat, or even the need to change out of work clothes!

Furthermore, the comparison with light activity is astonishing: one minute of VIA could match 50 to 150 minutes of light activity for major risk-reduction outcomes. While light activity is crucial for breaking up sedentary time, it cannot be substituted for the unique systemic adaptations triggered by true intensity.

Anti-Aging Mechanisms Driven by Intensity

The disproportionate efficacy of vigorous exercise stems from powerful biological signaling mechanisms:

-

Cardiorespiratory Fitness (VO₂ Max): VIA is the most potent way to increase , which is consistently cited as one of the strongest independent predictors of longevity [2]. High intensity structurally and functionally rejuvenates the aging heart and arteries.

-

Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Health: Vigorous movement is essential for driving mitochondrial adaptations, enhancing their function, and increasing their density—a fundamental marker of cellular youth and metabolic health [3].

-

Lactate as a Signaling Molecule: Far from being a mere waste product, the acute production of lactate during high-intensity work acts as a hormone-like signaling molecule, coordinating cross-talk between muscles, the brain, and other organs [4].

-

Targeting Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): Vigorous exercise enhances immune surveillance by mobilizing and increasing the proportion of cancer-destroying cells, such as Natural Killer (NK) and cytotoxic T cells, effectively helping the body eliminate CTCs and reducing cancer risk [5].

This evidence strongly supports protocols focused on intensity, underscoring the efficiency and profound anti-aging benefit of short, strenuous workouts. This would also explain why people say I look 20 years younger than my age, and I feel 30 years younger, and can outperform men 40 years younger. I have been doing this type of exercise nonstop as a lifestyle for the last 3 decades, so the proof of concept is quite strong.

To see a brilliant researcher do a “deep dive” into this subject, click here to watch Dr. Rhonda Patrick and Brady Holmer’s discussion.

References

[1] Stamatakis, E. et al. Wearable device-based health equivalence of different physical activity intensities against mortality, cardiometabolic disease, and cancer. Nat Commun (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63475-2

[2] Blair, S. N. Physical inactivity and all-cause mortality: new insights from the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. Sports Med (2009). https://www.cooperinstitute.org/research

[3] Hood, D. A. Mechanisms of Exercise-Induced Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Skeletal Muscle. Integr Med (2020). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19448716/

[4] San-Millán, I. & Brooks, G. A. Assessment of Metabolic Flexibility by Means of Measuring Blood Lactate, Glucose, and Fatty Acid Oxidation Rates. Adv Physiol Educ (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0751-x

[5] Shephard, R. J. Physical activity and the immune system. Sports Med (1998). https://www.gssiweb.org/sports-science-exchange/article/sse-151-effects-of-exercise-on-immune-function/1000

Lastly, another reason X Gym works so well, beyond our vastly superior methodology, is due to our training style. Every X Gym trainer goes through a rigorous certification process to learn our extensive methodology and philosophy. The chart below shows the expected results from these factors compared to other exercise choices, based on our own comparison data since 1998.

Copy of x chart