This is one of my longer posts, but it will be worth it – both as an education piece and also as a motivator to exercise. If you have a highly function Pre Frontal Cortex (PFC), you will have the attention span to finish this. If you don’t, you will find it difficult to maintain focus but the information you get out of this will certainly help with that too.

This is one of my longer posts, but it will be worth it – both as an education piece and also as a motivator to exercise. If you have a highly function Pre Frontal Cortex (PFC), you will have the attention span to finish this. If you don’t, you will find it difficult to maintain focus but the information you get out of this will certainly help with that too.

As time goes on, study after study after study shows the most effective, potent way that we can improve our quality of life and duration of life is exercise. This applies to our brain, body, internal organs, wellness, attitude, mood, and immune function to name just a few, which are all important to our quality and duration of life.

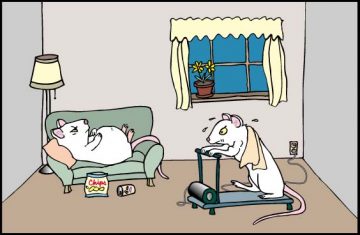

In 2011, Dr. Mark Tarnopolsky and his team of scientists studied mice with a terrible genetic disease that caused them to age prematurely. Over the course of five months, half of the mice were sedentary. The other half were coerced to exercise.

By the end of the study, the sedentary mice were barely hanging on. Much of their fur had fallen out. Their remaining fur had grown coarse and gray. Their muscles shriveled, hearts weakened, and skin thinned. Even their hearing got worse. “They were shivering in the corner, about to die,” Tarnopolsky says.

But the group of mice that exercised, genetically compromised the same as the sedentary mice, were nearly indistinguishable from healthy mice outside the experiment (aka the control group). The exercising mice had sleek and black fur coats, they ran around their cages, they could even reproduce. “We almost completely prevented the premature aging in the animals,” Tarnopolsky says.

That’s remarkable news if you’re a mouse. And though there are obvious differences between rodents and humans, Tarnopolsky has seen something similar happen in his patients, even those with extreme genetic diseases like muscular dystrophy. “I’ve seen all the hype about gene therapy for people with genetic diseases, but it hasn’t delivered in the 25 years I’ve been doing this,” he says. “The most effective therapy available to my patients right now is exercise.”

Tarnopolsky now thinks he knows why. In studies where blood is drawn immediately after people exercised, researchers found that many positive changes occurred throughout the body during and right after a workout.

“It’s unbelievable. If there were a drug that could do for human health everything that exercise can, it would likely be the most valuable pharmaceutical ever developed.”

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) came up with an intention to test the hypothesis that exercise is actually medicine, and even set aside 170 million for it, but this is stalled, unfortunately. They haven’t acted on it, so it looks like that won’t happen now.

EXERCISE DEFICIT DISORDER

The trouble is only 19% of Americans get the beneficial amount of exercise per week. More than half of all baby boomers report doing no exercise whatsoever, and 94 million Americans over age 6 are entirely inactive. These numbers are likely even worse than this, as they come from self-reporting surveys, where people are notorious for over-reporting activity and under-reporting calories eaten – not because they are lying – but merely because that’s how our brain bias works.

The consequences of a sedentary life are as well documented as they are dire. People with low levels of physical activity are at higher risk for many different kinds of cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, arthritis, low back pain, diabetes, and early death by any cause, to name just a few.

Despite public awareness campaigns, the health benefits of exercise have not been effectively communicated to the average American. Humans are notoriously bad at assessing the long-term benefits and risks of their lifestyle choices. Vague promises that exercise is “good for you” or even “good for the heart” aren’t powerful enough to motivate most people to do something they think of as a chore.

Humans are, however, motivated by rewards. That is why experts like Tarnopolsky are so focused on proving that the scientific benefits of exercise, such as anti-aging, better mood, less chronic pain, stronger vision, reduced stress, the list goes on. These effects are real, measurable, and in many cases, immediate, which is also something humans like.

Before doctors’ focus shifted to treating symptoms with drugs, their main goal was to keep people healthy and well. Even back in 400 B.C., doctors knew that diet and exercise were the best ways to do that. “Eating alone will not keep a man well,” Hippocrates famously wrote. “He must also take exercise.” For millennia, doctors were the vanguards of physical education–the original PE teachers.

WHEN EXERCISE BEGAN TO DIE

But in the early 1900s, with the rise of modern surgery and pharmaceutical companies, medicine shifted its focus from the prevention of disease mere treatment, with 85% of those treatments targeting symptoms, and only 15% targeting the actual disease, but little to no modern physicians are now targeting the underlying CAUSE, which is what exercise does.

Paradoxically, modern physicians de-emphasized exercise just as the modern Olympics swelled in popularity and colleges began building campus stadiums to accommodate America’s growing love for spectator sports.

The authors of a paper published in a 1905 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association mourned how many people were losing sight of the health benefits of exercise. “The men on the teams are the very ones whom Nature has endowed superabundantly with physical capacity, but on them, the physical director bends most of his energies while the average student is left to get his physical development by yelling from the bleachers.” Physical activity was no longer the medicine of the masses but the privilege of elite athletes.

When scientists studied exercise, it was to figure out how athletes could improve their peak performance–not how mere mortals could improve their health day to day. This gap persists. At a time when boutique fitness studios are more popular than ever, fewer people are getting the minimum recommended amount of exercise.

Worse, many U.S. schools have seen gym classes cut from the curriculum; more than half of high school students don’t have weekly PE classes, and only 15% of elementary schools require PE at least three days a week for the school year. The result: the majority of American kids and adolescents have so-called exercise-deficit disorder.

Meanwhile, childhood obesity rates have climbed every year since 1999. “You have whole generations that are soured on exercise,” says Jack Berryman, professor emeritus of medical history at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Researchers like Tarnopolsky and Marcas Bamman, an exercise physiologist who also wants to be part of the NIH study (if it ever happens), are hoping that their work will begin reversing those trends.

WHAT IS EXERCISE?

Think of all the different ways you can sweat and you might be surprised that each falls into one of just two categories. You’re doing aerobic exercise when your breathing speeds up, your blood flows faster, and your heart pumps more of it, shooting oxygen out to the tissues in the rest of the body. It’s the most popular kind among Americans, but only 20% also do the other type, strength training.

This is because cardio is easier than strength training, but it’s a shame more people don’t do it because to build muscle and strengthen bones, you must strength train. It’s simple too. You really only need to use your body weight as resistance, says Anthony Hackney, an exercise physiologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

That’s why things like X Gym, Yoga, Tai Chi, and Pilates (not just pumping iron at Gold’s Gym with the other bodybuilders) are excellent forms of strength training. “People always get the image of the big, muscular guy,” Hackney says. “We think of muscle strength and power as a 65-year-old lady picking up a gallon of milk, pouring a glass, and feeling comfortable.”

In addition to the heart, muscles, lungs, and bones, scientists are finding that another major beneficiary of exercise is its effects on the brain. Recent research links exercise to less depression, better memory, and quicker learning. Studies also show that exercise is the best way to prevent or delay the onset of Alzheimer’s, which is second only to cancer as the disease Americans fear most, according to surveys.

Scientists are quickly gaining knowledge as to why exercise changes the structure and function of the brain for the better. So far, they’ve found that exercise improves blood flow to the brain, feeding the growth of new blood vessels and even new brain cells, courtesy of the protein BDNF, short for brain-derived neurotrophic factor. BDNF triggers the growth of new neurons and helps repair and protect brain cells from degeneration. “I always tell people that exercise is regenerative medicine–restoring and repairing and basically fixing things that are broken,” Bamman says.

Repairs like this throughout the body may be the reason exercise has been shown to extend life span by as much as five years. Studies have also shown exercise slows the aging of cells. As humans get older and their cells divide over and over again, their telomeres–the protective caps on the end of chromosomes–get shorter. To see how exercise affects telomeres, researchers took a muscle biopsy and blood samples from 10 healthy people before and after a 45-minute ride on a stationary bicycle. They found that exercise increased levels of a molecule that protects telomeres. Exercise, then, slows aging at the cellular level.

EXERCISE ANS WEIGHT LOSS

For all its benefits, however, exercise is not an effective way to lose weight, data has shown, mainly because as fat is lost, muscle is gained, so the scale doesn’t show the whole story, and those tied to a scale might become discouraged.

This is why the X Gym has a $10,000 “scale” which goes far beyond just bodyweight. It also measures muscle, and even segments users into arms torso and legs so members can track exactly what is happening.

Some people even gain weight after they start exercising, whether from new muscle mass, a fired-up appetite, or both. “Some people say exercise doesn’t do anything,” says researcher John Jakicic of the University of Pittsburgh. “Well, exercise does a lot. It just may not show up on the scale.”

For those who do experience a fired-up appetite, it’s important to know what the body is really asking for. Water and protein, the two main ingredients of muscle, are what the body is requesting when exercise increases overall hunger. Unfortunately, when people don’t know this, they just eat “food” to satisfy that hunger, and if that’s mostly carbs (like the majority of Americans eat), then fat gain will happen.

THE TIME HACK

What’s more, emerging research suggests that it doesn’t take much movement to get the benefits or exercise. “We’ve been interested in the question of, How low can you go?” says Martin Gibala, an exercise physiologist at McMaster University. After all, if it were possible to reap all the health benefits of exercise in a tiny fraction of the time, who wouldn’t be compelled to give it a try?

Gibala wanted to test how efficient and effective a 10-minute high-intensity workout could be, compared with the standard 50-minutes traditional steady-state style. The micro-workout he devised consists of three exhausting 20-second bouts of all-out, hard-as-you-can exercise, followed by 4-minute recoveries. In a three-month study, he pitted the short workout against the standard one to see which was better.

To his amazement, the workouts resulted in identical improvements in heart function and blood-sugar control, even though the traditional workout was five times longer. “If you’re willing and able to push hard, you can get away with surprisingly little exercise,” Gibala says.

Not everyone can (or wants to) do this high-intensity interval training style or HIIT. Many people would gladly bounce around in Zumba class for an hour to avoid enduring even a minute of HIIT style. But considering that a lack of time is the top reason people say they don’t exercise, a workout far shorter than what’s generally recommended could be a strong motivator. This is why X Gym is so successful, with its 21 minute workout that’s equivalent to about 3 hours, thanks to PJ’s research-based methodology.

WHO SHOULD EXERCISE?

Not every type of exercise will work for every person, of course, but a growing body of research indicates that very vigorous exercise (like the interval workouts Gibala is studying, and X Gym) is, in fact, even appropriate for people with different chronic conditions, from Type 2 diabetes to heart failure. That’s new thinking because, for decades, people with certain diseases and even pregnant women were advised not to exercise.

Now scientists know that far more people can and should exercise. A recent analysis of more than 300 clinical trials discovered that for people recovering from a stroke, for instance, exercise was even more effective at helping them rehabilitate.

Dr. Robert Sallis, a family physician who runs a sports medicine fellowship at Kaiser Permanente Fontana Medical Center in California, has prescribed exercise to his patients since the early 1990s to reduce his medication prescriptions. “It really worked amazingly, particularly in my very sickest patients,” he says. “If I could get them to do it on a regular basis–even just walking, anything that got their heart rate up a bit–I would see dramatic improvements in their chronic disease, not to mention all of these other things like depression, anxiety, mood and energy levels.”

Older people, too, can benefit from strenuous exercise. Until now, all the recommendations for increasing bone density have included low-repetition, high-weight types of training, says Jinger Gottschall, associate professor of kinesiology at Penn State University. “But this just isn’t feasible for a lot of people. You can’t picture your grandma going in and doing that.” Luckily for Grandma, Gottschall’s team found that lifting lighter weights for more reps also improves bone density in key parts of the body, making it a good alternative to heavy lifting. X Gym style uses light weights too, but with longer time under tension than traditional training, which adds a cardio aspect, making it a combo exercise, which contributes to its unique time-saving hack.

It’s becoming evident that nearly everyone, regardless of age or condition, benefits from exercise. And as scientists learn more about why that is, they’re hoping that those early 20th century missteps–the move away from our being bodies in motion–will be reversed. They’re also hoping that the messaging around exercise gets simpler.

“People think now, because of the health club and fitness movement, that in order to exercise you need to join a fancy club and wear fancy clothes,” says Berryman. In fact, some of the best exercise, research is showing, doesn’t require a gym membership at all. The X Gym App, for instance, can be done anywhere anytime, with little equipment, or even none at all.

TARNOPOLSKY STUDY RESULTS

Back at McMaster University, Tarnopolsky and his team have done autopsies on mice from their new study, and even though the scalpel-wielding scientists are blind to which groups the mice were in, they can tell with certainty which animals were allowed to exercise and which were sedentary. “You open up the sedentary mice and there’s fat all over the place,” he says. About half of those mice have tumors. “They just look god-awful.”

As for the mice who hit the wheel every day? “We haven’t found a single tumor,” he says. “I think if people saw, they’d be pretty motivated to exercise.

Click here to see the source for much of this information.